Chapter 5

Hill Country

First Axiom: A Tangible Purpose That Is Narrow and Transparent

Miller’s Tavern in Murrayfield, Massachusetts had thick hollow walls with hidden staircases and hiding places for slaves under the barn floor. For many who took this clandestine route to freedom it was known as The Gateway—to Canada and freedom. Murrayfield was an ideal location for an underground railroad station, as it was situated among rugged hills, unnavigable rivers, and difficult dirt roads—conditions that favored people on foot.

Located within two hours of all four of the largest cities of New England, Murrayfield—now called Huntington—remains charmingly and beautifully rural.

During a period of public school regionalization Huntington joined with six neighboring rural towns to form The Gateway School District, an unpopular but necessary decision taken to maintain state funding.

The people who live in the region defined by theses seven towns call it The Hill Country.

Karen Anne Zien and I were driving back to Boston. We had spent the night at the home of a Gateway Building Committee member, who lived off the grid. In the loft of her barn there were 50 golf cart batteries that saved electricity from solar panels. A Honda generator sat idle waiting for the next cloudy December. Gas lamps in the kitchen and dining room provided 19th century ambiance. I found this so intriguing – so close to Boston – that I had trouble focusing on the issue at hand.

The issue at hand was that the Hill Country desperately needed a new elementary school. An exhausted building committee had worked for years developing plans, holding hearings, placing articles on town meeting warrants, and doing all the traditional things that lead to decisions and the allocation of funds in town governments in Massachusetts. When these failed, building committee members baked cookies, held teas, formed circle groups, and conducted structured dialogue sessions. This led only to more heartfelt despair. Now they might take a chance on us, if we are willing to write a proposal, they are willing to accept it, and we agree to reduce or eliminate our fees.

“Are you willing to do this pro bono?” I asked Karen Anne.

“I was thinking of bartering,” she said. “They have some things they could offer—maple syrup, weekends in the country—and you could get advice on making your house independent of Green Mountain Power.”

“Well, it’s moot anyway. I don’t see how we can help them. The conditions they have set for our help are just too stringent,” I volunteered, hoping Karen Anne would not be too disappointed. We had met in a seminar group and were exploring ways in which we could learn in depth about each other’s specialty. Her specialty was innovation. She had found this situation to learn about mine—working with people representing all parts of a complex issue in one room at one time.

After a silence she said, “OK. But just tell me just one more time why we can’t help. It seems like the perfect situation to use your tools. Why not Future Search?”

“Well, my most important tool is building a shared understanding of the context of their situation—how they got into this mess, and what the mess looks like right now—and that generally takes seven or eight hours. After that, we normally move on to future possibilities, the discovery of common ground, and action planning. That takes at least another eight hours. In this situation, I’m pretty sure we’re stuck with eight a.m. to four p.m. on a Saturday, period. It’s autumn, the harvest has to be brought in, cows always have to be milked, the whole region is fed up with this issue, and the people are exhausted and are setting boundaries on just how much energy they are willing to contribute to a hopeless cause.”

“Let’s skip the talk about the past and the present. They’ve been working on this for years, and they know all that.”

“Can’t do that. The process of eliciting collaboration requires them to be actively engaged in developing a shared understanding in the moment. They probably have heard it all and know it all but not the way we need them to know it: together, as a unit. Also, you can’t get the collaboration response we need from a slide presentation or by reading through minutes of all the hearings and meetings.”

Silence. I look at the hills, the almost dry stream beds, and the twittering Aspen leaves.

“Gil, I know where they should build the new elementary school!”

“So do I!”

“Huntington!” we said at the same time.

“So what?” I asked dumbly.

“So what? So what! So…it means we don’t need four hours to decide what action to take. If it’s a no-brainer for us, then they should be able to figure it out in half an hour.”

I laughed so hard, I spilled my coffee all over the dashboard. “You want us to design a twelve-hour meeting of which eleven hours and thirty minutes is spent getting ready to work and thirty minutes is spent working?”

More laughter.

“No. I want us to design an eight-hour meeting of which the last thirty minutes is spent doing the work.”

“Karen Anne, you forgot the four hours we’ll need to build their vision of the future.”

“Not our job. Not even appropriate in this situation. They are at war with one another, three hundred thousand pumpkins have to be dragged from the fields, and there is the relentless pressure of cows and their udders. Broadening the discussion will just add to their burden.”

“So we need to stick with a narrow task, the narrower the better…Do you think that the ability to make just one decision together will transform the community?”

“Do you want a ten-year supply of maple syrup?”

***

We took on the challenge. We did our due diligence. We interviewed more people to make sure we understood enough about the situation, met with the building committee to share what we thought would work and get their reaction, and helped those in charge of logistics mobilize. But basically, we stuck with Karen Anne’s idea of an eight-hour meeting, of which thirty minutes would be allocated to decision-making. In a nutshell, here is what happened.

We asked the building committee to invite a delegation of seven people from each of the seven towns. We asked for a town official, a parent, a student, a teacher, a senior citizen, and two other people of any orientation. We promised coffee at 7:30 a.m. and that the work would be done in time for them to get home for the evening milking. We explained that everyone needed to be there the whole time—no wandering in and out.

By eight on a crisp autumn Saturday, in a school cafeteria, we were under way. We had chairs arranged around seven tables, one for each town delegation. I found myself looking over the participants to catch their moods. Were they nervous, resentful, optimistic, defiant, ambivalent, excited, or bored? It was hard to tell; they were all on good behavior.

The building committee chairman explained that our purpose was to talk about the relationship of their towns to the school district and to see if we could come to agreement about a new elementary school location. He introduced Karen Anne and me.

Karen Anne asked people to stand one at a time, to give their names, to state their relationships to the public schools, and to tell the whole group what they loved most about life in the Hill Country. They took this last question very seriously, and we gave them time to share what they loved: the beauty, the quiet, their independence, midwinter bonfires, quilting, wildlife, their library. I relaxed as I heard common ground emerge on something that was simple but important: why they lived where they lived.

I gave them their first task assignment. Each town delegation was to come to agreement about three questions. They were to write their answers on three separate large wall charts with the name of their town at the top. We based the following three questions on a few things we picked up by sitting in on a building committee meeting:

- What are the four most important things to your town in deciding whether or not we should preserve town elementary schools?

- How would you characterize a really smooth working relationship between your town and the district—a relationship capable of dealing with all the difficult dilemmas and issues that we will face in the future? What specific recommendations do you have?

- What are the three most important things needed by your town in order to obtain support and approval for a proposal from the building committee?

We had intended this to be hard work for these delegations that had never before worked together, and it was. We stayed out of their way, and when seven sets of charts were hanging on the cafeteria walls, we suggested a break. We chatted with a few parents and town officials. They were into it.

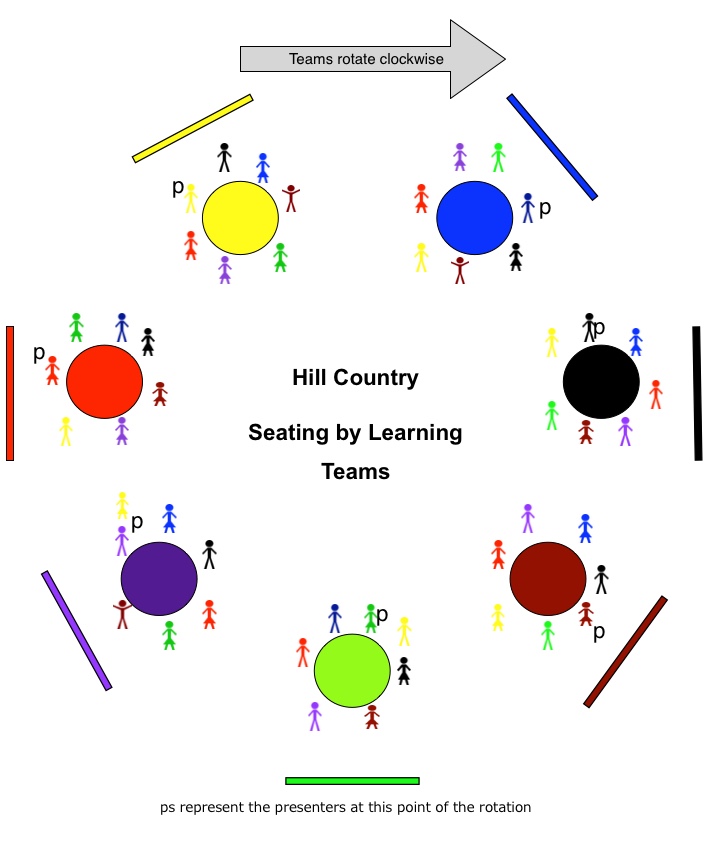

After the break, we had each delegation assign a number between one and seven to each of its members. We then had everyone stand and asked that all the “ones” move to table one, all the “twos” to table two, and so forth. We explained that the new groups that had been formed were learning teams whose job would be to study the responses of the seven delegations to the three questions. Our limited time meant that they would not be seated again as a town delegation. It was a little like giving them a one-way ticket to consort with the enemy.

We gave the learning teams twenty-five minutes to study the work of the town delegation whose wall charts were closest to where they sat. We asked that the first ten minutes be a presentation by the member of the learning team from the town delegation that created the report. The remaining fifteen minutes was to be used for questions and discussion.

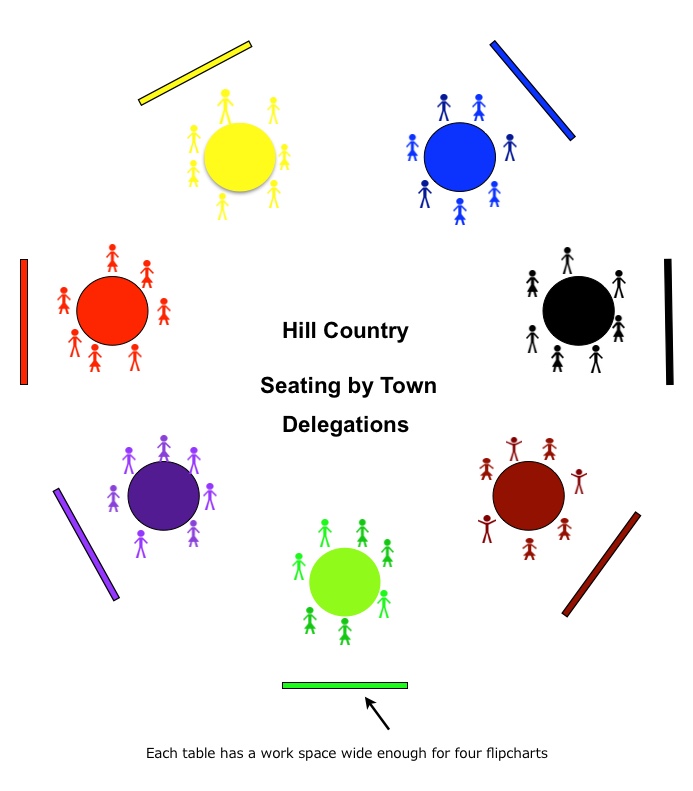

At the end of twenty-five minutes, we had everyone stand and asked that the learning teams move to a new location and study the work of another town delegation using the same format. In four hours, all the learning teams had studied all the town delegation reports and had had lunch. In the process, every person in the room had made a ten-minute presentation on their town’s perspective, including the sixth-graders, the grandparents, and the reticent. Figure 1 shows what the school cafeteria looked like when the town delegations were working on their assignment.

Figure 1. Hill Country seating by town delegations.

Figure 1. Hill Country seating by town delegations.

Figure 2 presents what the school cafeteria looked like when the learning teams were studying the work of the town delegations.

Figure 2. Hill Country seating by learning teams.

Figure 2. Hill Country seating by learning teams.

As a safety measure, to make sure there was a shared understanding of what was happening outside the Hill Country, we inserted an eighth table into the rotation (not shown in the figure). Karen Anne and I stationed ourselves at that table, and when a learning team arrived, we spent twenty-five minutes with them creating (or adding to) a two-dimensional map of the trends and forces outside of Hill Country that could possibly have an impact on their future. We noticed a lot of good-humored, animated talk within the learning teams while they had their brown-bag lunches.

Next, we asked the learning teams to reflect on their time together and to identify three or four themes they discovered among the town delegation reports. Each team was allotted three minutes to make a verbal report to the large group. Karen Anne and I held our breath but were rewarded with what we had anticipated would happen. The following are a few snippets of the large-group conversation that followed the verbal reports:

“We all want the same things.”

“All seven towns recognize that we just have to give up individual town elementary schools…and as we talked about it, we discovered some ways that would make it easier on the kids.”

“The differences between the town perspectives—once the different ways of saying things are understood—are small, really negligible.”

Seizing the moment, we moved on, asking two more questions of the learning teams: What resolution do they see to the dilemma of the new elementary school? Where should it be located?

Huntington, Huntington, Huntington, Huntington, Huntington, Huntington, and Huntington.

I could already taste the maple syrup. The building committee had the information it needed to get approval for a plan and would have the support of the participants who made up the town delegations. The meeting had run a little late. But the cows would have to wait a little longer before they were milked, as the assembled community broke into a spontaneous round of appreciation and forgiveness, producing more than a few tears. The affection they felt for their town had burst through the boundaries and encompassed the whole region, at least for today.

Questions

Q: What happened to the conflict? You said they were at war with one another. Did you know ahead of time that this would work? What were the odds? How did you come up with this specific set of activities? Why didn’t the other things that they tried have a similar effect—the hearings, the community circles, and the dialogues? What were you looking for when you interviewed people prior to creating your design? It sounds like you didn’t do much at the meeting other than give people tasks to do. Is that accurate?

A: There may never have been a rational conflict. They were having trouble letting go of individual town elementary schools. They feared for the safety of their young children. The “war” was just an expression of their angst.

We were pretty sure it would work. But there wasn’t much of a downside. At worst, it would be another well-intentioned effort to break a deadlock over the location of the new school, which would create some new relationships across town boundaries. The client had some anxiety about doing this, but their anxiety may have been more rooted in an innate fear of large groups than in the reality of the situation at hand.

We expected our meeting design to elicit the collaboration response in this community, and it did. The community circles and dialogues never had the whole system in one room at one time and didn’t comply with our eight key axioms, which we’re just beginning to explain.

As we listened to people, we were looking for characteristics of the district and this situation as a whole. We pretty much ignored information provided about specific individuals and specific relationships, except as it described the whole.

We’ve learned from experience that the less we do in meetings, the more the participants take ownership of the results. As we have structured meetings to make participant leadership more visible and our leadership less visible, the number of people who have come gushing up to us afterward with profuse thanks for our brilliant work has dropped precipitously, but it’s a small price to pay for the deeper satisfaction of watching people find their own way of advancing the common good.

In summary, clarity of purpose is essential to eliciting collaboration. Group development and group performance cannot proceed without it. Purpose should be as broad as it needs to be but no broader. The narrower the purpose, the faster the group matures and the faster it performs.

Only have a little bit of time? Find a smaller purpose.

Q: Besides clarity and not being too broad, are there other criteria for a good statement of purpose?

A: A good purpose is something important to the whole system, and if patrons or customers are part of the system, then something important to them.

Q: How about an example?

A: A meeting about upgrading the technology of a library will be a better meeting if the benefits or impacts to the patrons are evident in the purpose. And of course, the meeting will be better if there are patrons in the room.